Poe Elementary School bombing, Houston, Tx. 1959

Shared with permission via Houston History facebook:

A RIVETING EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT BY GORDON L. ROTTMAN: At 10:10 AM, On September 15, 1959 - On The Blackboard is Written - Our News: This is Tuesday, It is Sept. 15, 1959, It is Warm and Sunny, Cliff is Not Here Today...

Mrs. Kirby, our 5th grade teacher, stopped mid-sentence when the explosion boomed a shock wave through the school. Shattering glass rattled from the far side of the building. Our clock fell from the wall and a linear cloud of dust puffed around the room from the baseboards. One boy nearest the door leapt up and headed for it. Mrs. Kirby very coolly said, “Be seated, the fire alarm’s not gone off.”

The moment he sat the alarm sounded and out we went as we had practiced monthly. We filed down the 6th grade hall, each class in-turn, and though the building’s end doors onto the playground.

We stepped into hell!

To our right was the asphalt hard-surface area and the first thing that came to my mind was that it looked like a burned trash pile spread across the double-basketball court. Lying closer was a young boy, his clothes blown off, his intestines spilled (I promise not to be any more graphic—it’s just that that was my first realization that people were hurt.) I realized then the smoldering trash pile included people.

The 5th and 6th grade teachers quietly moved us to the playground’s far side and we sat by class on the softball diamond, backs to the carnage, not that everybody didn't turn to look. I saw a few injured kids staggering amid the ruinage along with a tall, thin teacher doing what she could.

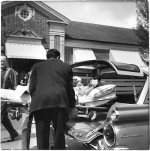

Our class exited the school from the doors at the upper left. This is the body of the first child I saw. A desperate mother searches for her child.

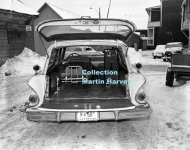

The first on the scene were fire trucks, then police, and then more cops. Ambulances arrived, but not that many. These were old-style station wagon-like ambulances, not the high-tech EMS ambulances we know today. There were no EMTs then. Ambulance crews merely scooped up the injured and hoped they could get them to a hospital alive. Most belonged to private ambulance companies or hospitals. ERs were nothing like they are today and they certainly were not prepared for anything like what had just occurred. Fortunately the main county emergency hospital and other hospitals were within 15 minutes.

The hard-surface area with the school in the background. Miss Johnson was moving the kids to the building wing on the left behind the trees when the bomb detonated. I don’t know if it was confusion, shock, or the steadiness our teachers displayed that keep things under control. My parents were among the first to appear as they went into open their restaurant later in the morning. We lived three blocks away. Unlike today there was no lock down. Parents got their kids and went home. Some kids walked home on their own—everyone lived close—there was no busing then. We even took a neighbor kid home as his parents were at work. You simply told the teacher and left.

I wasn't rattled a bit and that perplexed me. My only confusion was that I didn't know what to do the rest of the day. I ended up going to Kemah southeast of Houston with my dad. He had a restaurant there and it was strange hearing customers discuss what I’d seen a couple of hours earlier.

Some ambulances had to park in the school's front circular drive to load the injured. No EMS ambulances in those days. The metal awnings had recently been installed to shade the windows as there was no air conditioning.

Okay, what happened? A somewhat mentally disturbed man, 47-year old Paul Orgeron, had divorced his wife and abducted his son, 7-year old Dusty. Orgeron had brought his son to the school earlier to enroll him, but was turned away. He had no birth certificate or immunization records. The staff hadn't felt he was a problem other than acting very confused and didn't know his son’s former school’s name or the New Mexico town it was in. He soon returned, but instead of entering through the front, he went on the playground while 2nd grade recess was underway. Some kids though were inside taking assessment tests. In fact two girls from our class were detailed to help the teachers on the playground.

With son in tow and carrying a briefcase, Orgeron approached a 2nd grade teacher, Miss Patricia Johnson, and passed her two incomprehensible notes. She was concerned about his manner and noticed a doorbell buzzer on the briefcase’s bottom. Another teacher, Miss Jennie Kolter, sensed trouble and came to the scene. Orgeron wanted Johnson to gather the children around. Instead, she sent two kids to fetch the only adult male in the school, James Montgomery, the custodian, and the principal, Miss Ruth Doty. While Kolter talked to Orgeron, Johnson discreetly herded kids away. Doty, a very stern and strong-willed woman, feared and admired by us kids, took charge and began trying to get Orgeron off the school grounds.

It’s not clear what happened. Orgeron set the briefcase on his foot. It’s thought that it slipped rather than being intentionally set off. Six dynamite sticks detonated. Orgeron was disintegrated, his son shattered, Kolter and Montgomery blown apart, and two 2nd grade boys killed. Miss Doty was terribly injured and almost lost a leg. She had been standing behind the others. Two nearby boys each lost a foot and 15 other students were injured by blast and asphalt gravel including the two girls from our class who were helping get the kids away. They were among the most seriously injured.

At first, since they couldn't find Orgeron’s body, the police thought he might still be on the grounds. His car was located and found wired with dynamite to detonate if started. He had purchased 150 sticks in a New Mexico hardware store—you could do that then—which were never located. It took time to piece together events leading up to the bombing and some questions were never answered.

As I was able to leave early, I didn't see what arose when “every” fire truck, ambulance, tow truck, cop, reporter, and TV crew in the city showed up. Since there had been no preparations for such a catastrophic event, the teachers’ initial control evaporated. Frantic parents had to park blocks away as there was no place closer. Ambulances had difficulty getting through jam-packed streets. Parents ran all about trying to find kids who had been taken back inside. The National Guard was called to secure the school, as well as others that received bomb threats. Realistically, even if practiced to any degree, there’s little that could have been done to control it better.

How was it different from today? The next day school was open. About half the students attended with more returning each day. Mosquito-control trucks fogged the grounds to keep flies down as there were small body parts on roofs and in trees. We took a minute to bow our heads in silence. The following Monday all students were back. A couple of weeks later we had had a simple memorial service in the auditorium with Cub Scouts posting the flags. There was no army of counselors. No TV crews seeking interviews. No closing the school for the rest of the year or calls to tear it down. Not a single law suit. We moved on. The hard-surface area was re-blacktopped and a chain-link fence installed around the playground. In October the two boys who’d lost a foot led the Halloween Festival parade in a go-cart. Our two severely injured girls, Martha Jo Mullen and Leah Tomlinson, returned and were applauded at lunch. Months later Miss Doty returned as principal and remained until she retired. New elementary schools were named after Miss Kolter and Mr. Montgomery. Occasional bomb threats were phoned in and each class was assigned garages at nearby homes for shelter as winter was coming on. Neighbors left their cars out so we could use the garages. We moved on. Every few years the local paper does a brief write-up on the anniversary, virtually a copy of previous years.

As a personal note, the hero of the day was Pat Johnson who never received the credit she was due. Thirteen years later, after returning from Vietnam, I visited the school and looked up Miss Johnson. She’d been my 2nd grade teacher. She was still teaching 2nd graders. I had to tell her something. I’d seen some real heroes; real soldiers who kept steady no matter how bad things got. I told her she was a hero, she’d kept cool, did all the right things—recognized a threat, got the kids away, sent for help, and then took care of the injured and she was steady though out. It was her I’d seen on the smoldering hard-surface. Pat and I became close friends. It was an honor to have known such a woman.